How do artisan's document their own work? How can we help?

A large part of my work at Khamir has been to help the outside world learn about the artisans of Kutch through highly visual exhibition websites (www.exhibitions-khamir.org). But what about the artisans themselves? Living in isolated villages, they are unlikely to have the data plans, the language skills, or the interest in seeing a product designed for a cosmopolitan, English-speaking audience. But could there be a way for artisans to create an online record of their own work, for their own purposes? Would there be value in doing so?

During field research with the Meghwar communities, I interviewed leather artisans about their thoughts on Khamir’s archiving and documentation practices. Most acknowledged the benefits of educating a global audience, but none felt that Khamir's digital or physical records had a direct impact on their daily lives.

Mayabhai, Dholavira

“Our craft is very present and alive in our lives here, so we don’t feel the need to save anything. It is our way of life. It is innate for us. Only for teaching purposes or if someone from outside comes to ask and learn about this craft, for them all this information will be a helpful entry point into our world,” said Aanchalbhai, of Sumrasar village. Mangalbhai, of Gandhi Nu Gam, also saw the advantage of educating outsiders: “[Documentation] will create good awareness for visitors who might have their own input for new designs. So it will benefit us too, I think.”

When pressed, several leather artisans revealed that they'd been privately documenting their work for years. Older artisans kept patterns and photos to preserve techniques for future generations. Younger artisans took cell phone snaps of their designs to show to buyers.

Mayabhai, of Dholavira, said, “The younger ones don’t have a clue about how we used to work before. If you tell them today that we used to tan and dye leather in our village before, they will not like it, and they will feel embarrassed.”

Basar bhai, Hodka, mentioned that “We have taken photos and I have a small collection. I have told other artisans that we should carefully store our designs because twenty years from now, someone will find them useful.”

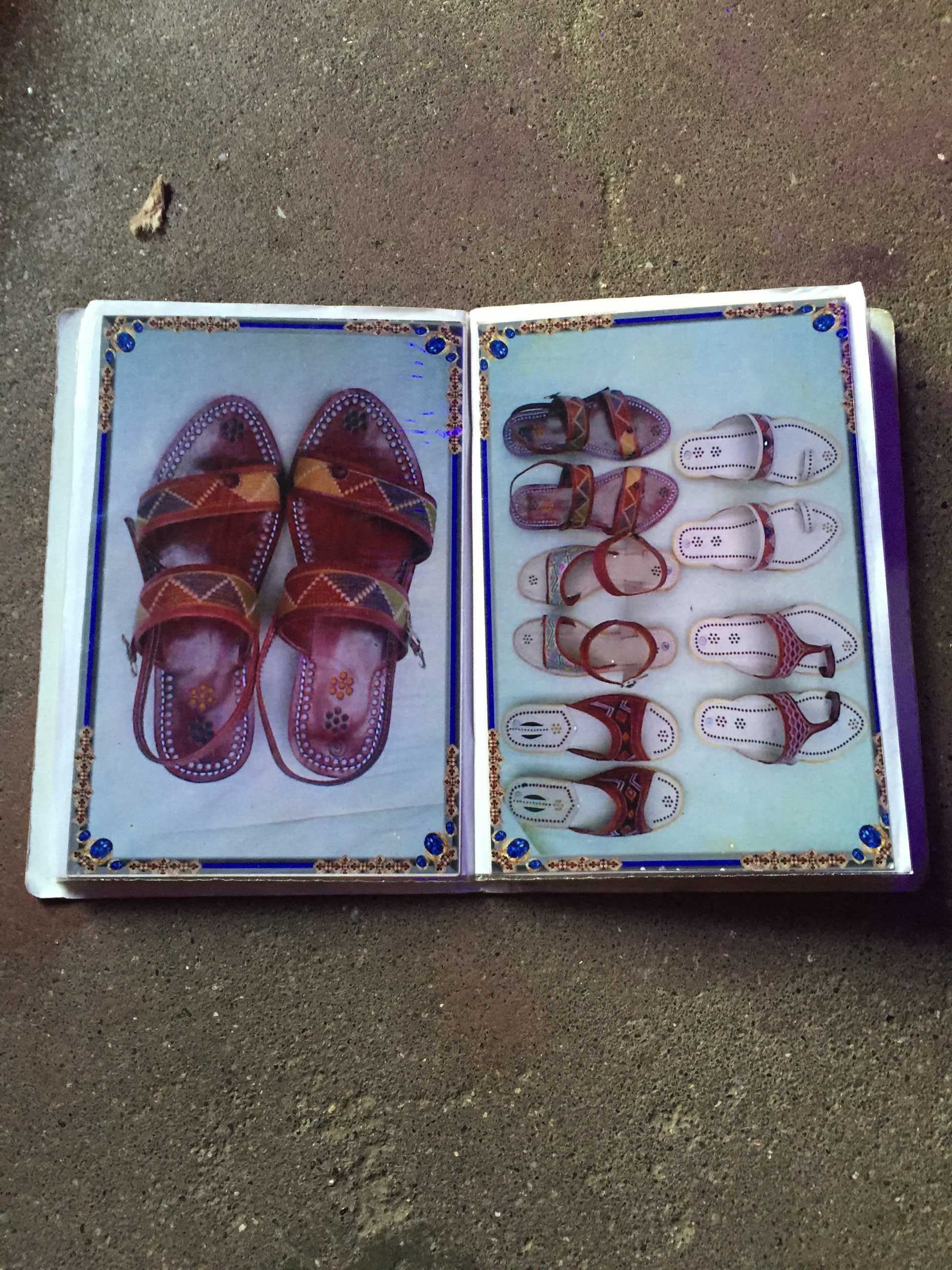

Trilokbhai, in Pragpar, pulled out a small photo album from his trunk of tools. “I took photos of all my samples for the studio so that people could see the different designs. I made two photo albums. I was introduced to this practice by my friend, to preserve my designs,” he explained.”

Quite a few of the artisan I interviewed felt that technology could play a role in helping facilitate their communication with buyers. “The youth are now more skilled and competent…they can handle technology so well,” said Mangalbhai, Jura. “They want mobile phones that look sleek, that have Whatsapp.” Jemalbhai, Hodka, shared that if anyone wants to see his designs, they simply call his phone and he will text them images. “With the help of the internet, the young people send photos across to clients and buyers,” said Trilokbhai.

“People’s fashion choices are being exercised. As artisans who want to sustain ourselves, we have to keep up with demands and global trends,” Najar Khetsinh Munjabhai told me in Nirona. Jemal bhai concurred. “We have to see what designs and products are most in demand so that we can remain economically viable,” he said.

But what about sharing their designs within their own community? I found that keeping up to date and sharing designs were considered important - but so was privacy.

Older artisans tended to be more worried about protecting their intellectual property than they were about staying current. “So many people have photos of my products and they claim it is their own work. And life is like that these days, no one cares about the real artisan, the fake ones get all the attention. I had so many photos, but people took them away with them,” said Ranabhai, from Hodka. Basarbhai told me that he doesn’t like to show his personal archive to outsiders, because “there are some people who will take photos of these things and exploit them without understanding the significance to us."

“A lot of designers are strict about circulating their designs,” said Trilokbhai. “It is true, a lot of newer artisans have begun to copy our designs and sell it for cheaper. I, however, have no objection, because the design takes effort, time and practice to perfect. I don’t think that someone can steal my design just by looking at it.”

To summarize my findings:

- Artisans do document their own work

- They use this documentation to preserve their crafts and connect with buyers

- Opinions on sharing designs vary and the ability to maintain privacy is important

- There is significant acceptance of mobile phones and the internet as tools to help their sales

The leather artisans, of course, are just one community in Kutch. But they are among the more marginalized and economically depressed groups, so I am taking their thoughts on technology and documentation as indicative of a fairly widespread acceptance of these practices. Anecdotally, the weavers and the block printers of Kutch, many of whom are quite prosperous, are very comfortable using mobile phones to send photos of their work to buyers.

There is currently no documentation tool that would allow artisans to record and share their work in a way that serves the dual purposes of educating the next generation and easily sharing their work with future buyers. I have an idea to help fill the gap. I am working with Payam Azadi, a software engineer who has donated his time to the project, on developing a mobile database for artisans that will function as follows:

- Artisans send text and photos of their work by Whatsapp to a predetermined number.- The content sent by Whatsapp is associated with an individual artisan and populates a database accessible by Khamir staff.

- The database can be used by Khamir staff for education and research purposes. They will have a live account of what new designs and craft evolutions are taking place.

- The database is also visible from the front end as a lightweight mobile portfolio for artisans. Each artisan can share a page of the work they've sent from their Whatsapp number.

- The front end can be public, password protected (so that artisans can send the page with a password to a prospective buyer) or visible to Khamir staff only, as each artisan prefers.

Below I've shared the wireframes for the database, which function as visual outlines for content and functionality.

Initial sketches of user flows and wireframes