Introducing digital tools to a rural nonprofit

Over four years working in New York, I’ve seen how some of the world’s leading philanthropies are taking the plunge into digital communications, investing more on websites, mobile-based tools, and interactive material.

How can smaller nonprofits take advantage of the internet and the prevalence of mobile phones not only to spread their message, but to actually improve their programs? I came to India this year to see how I could apply my knowledge of nonprofit branding, and UX design to an organization that is far more grassroots, and far less funded, than some of the large NGOs that were my clients in New York.

Khamir, my host organization here in Bhuj, is a nonprofit that supports artisan communities across Kachchh. Before getting here I struggled to understand exactly what Khamir did - an obvious first target for improved communications After working here for five months, I describe Khamir’s central goals as:

- Education: bringing awareness to local crafts with exhibitions, publications, and school visits

- Preservation: archiving and documenting traditional techniques

- Trade facilitation: providing credit, raw resources, marketing, and sales support to artisans

- Innovation: bringing in designers from around India and the world to help traditional crafts evolve to meet new market demands

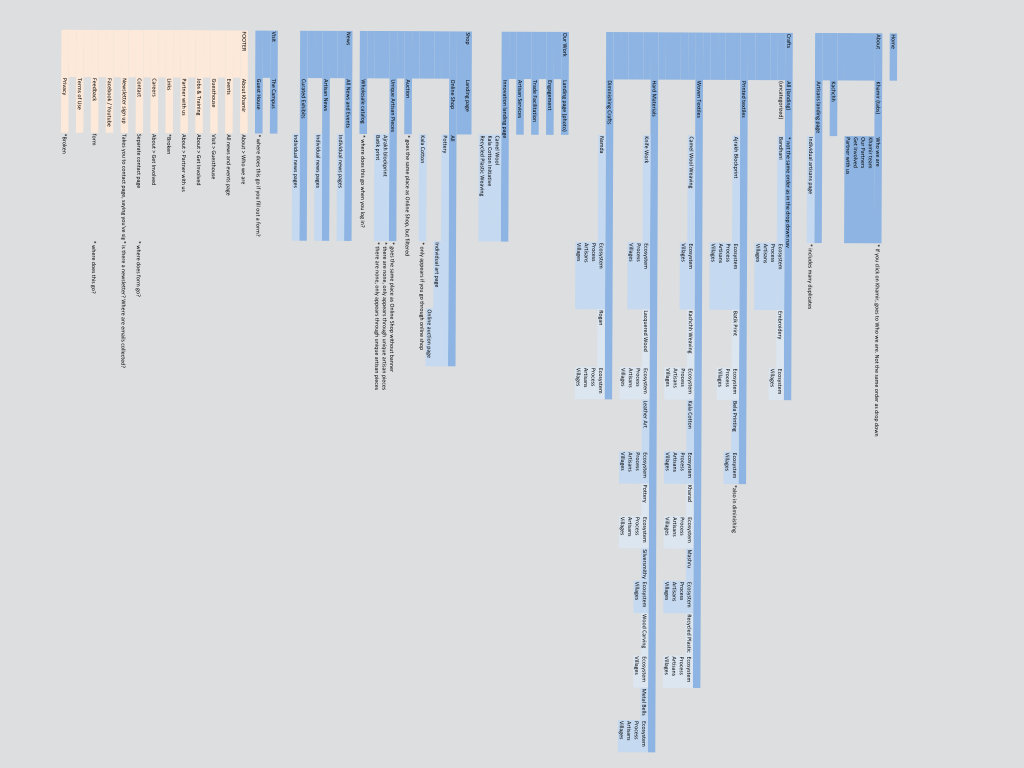

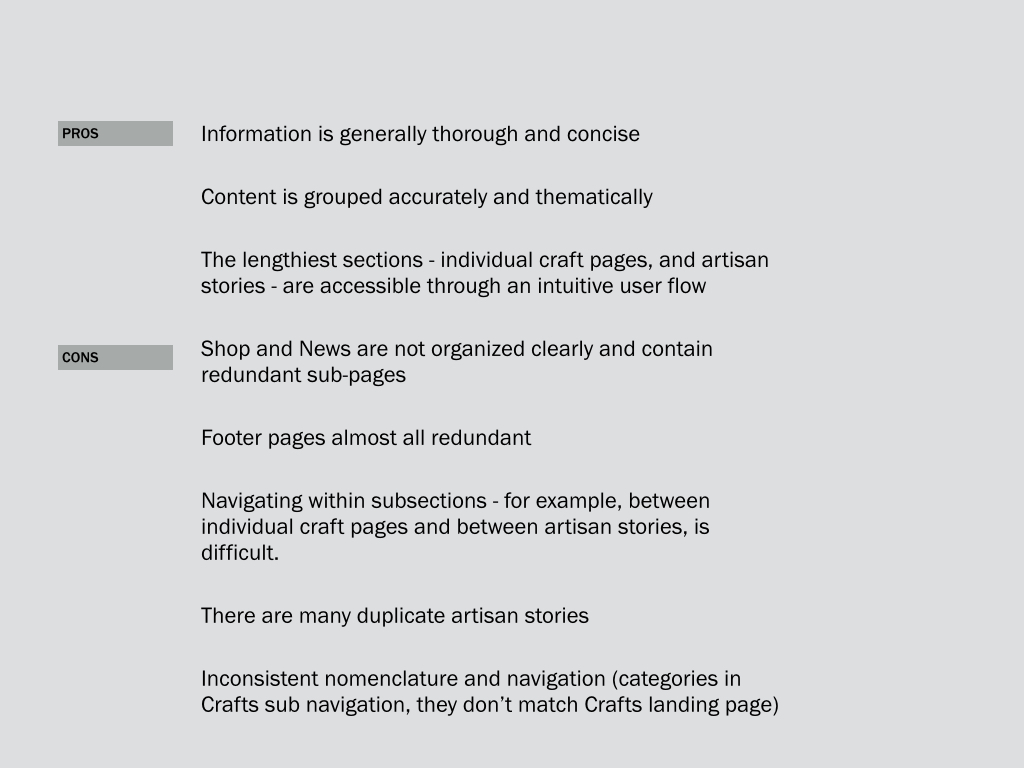

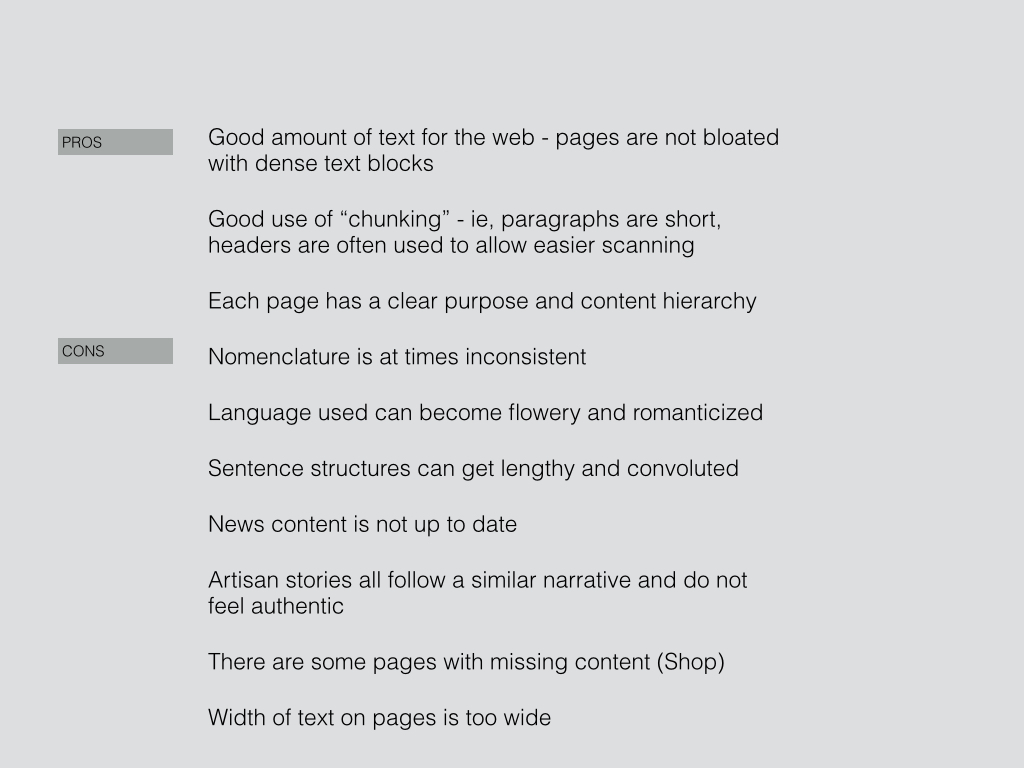

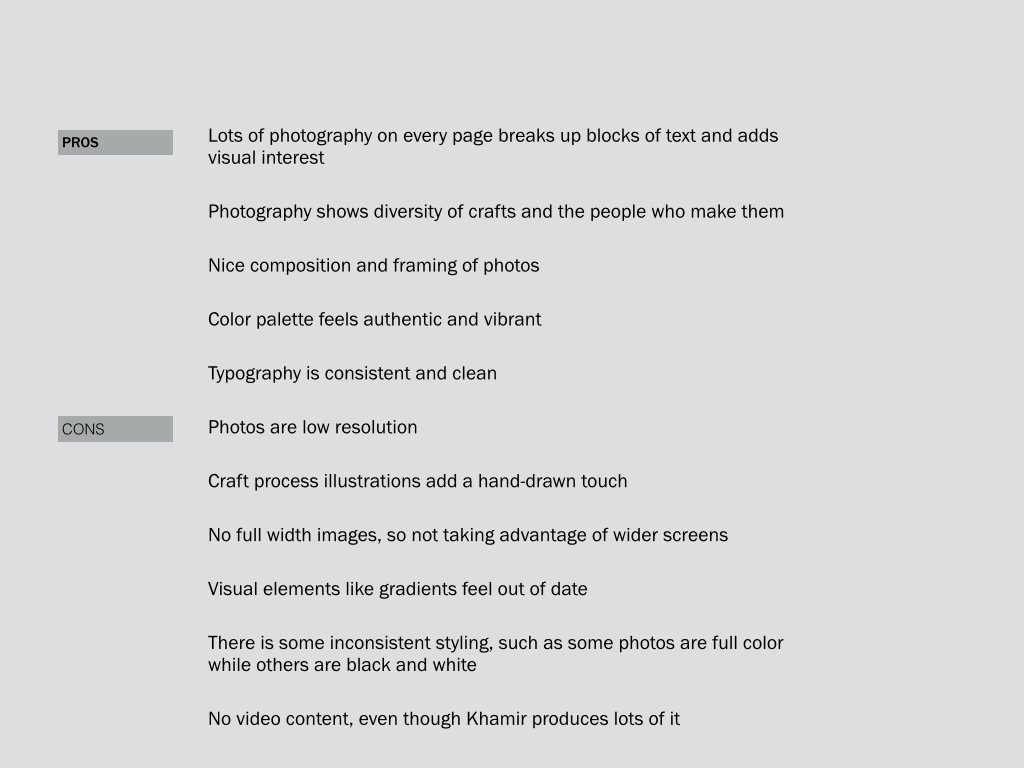

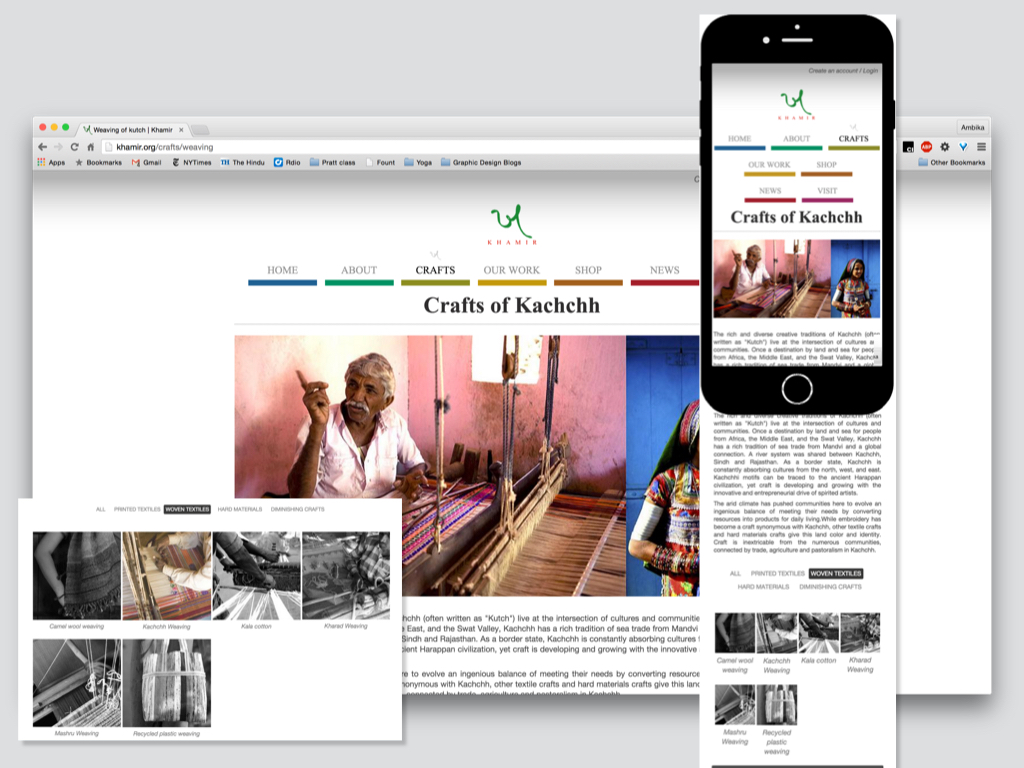

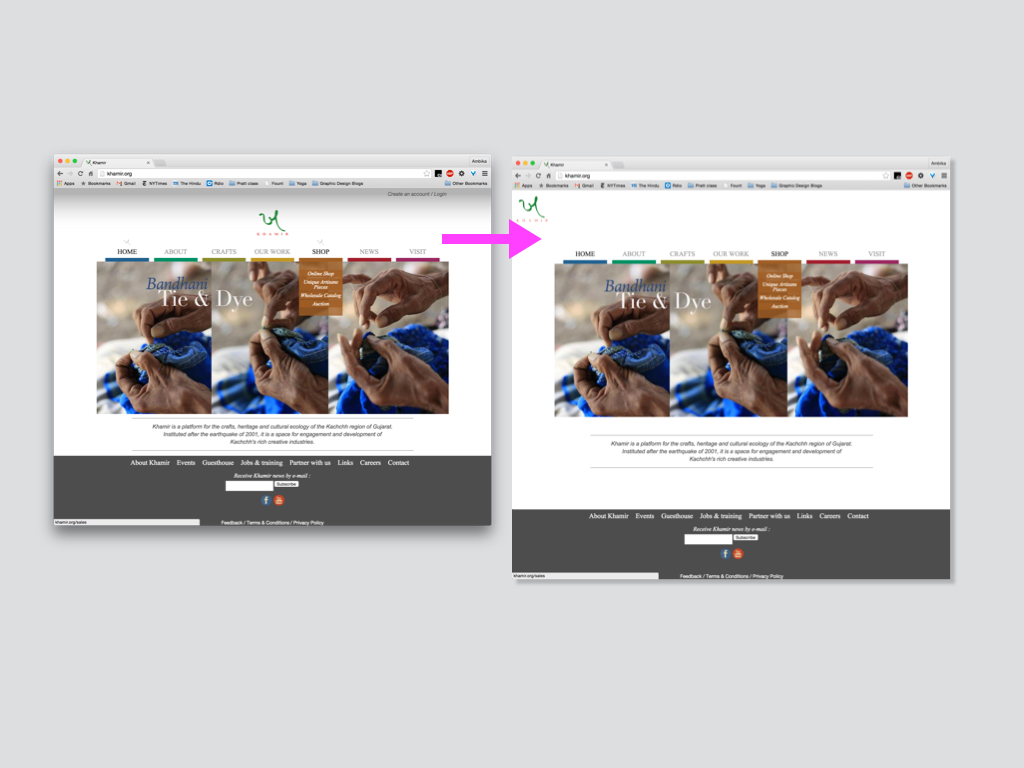

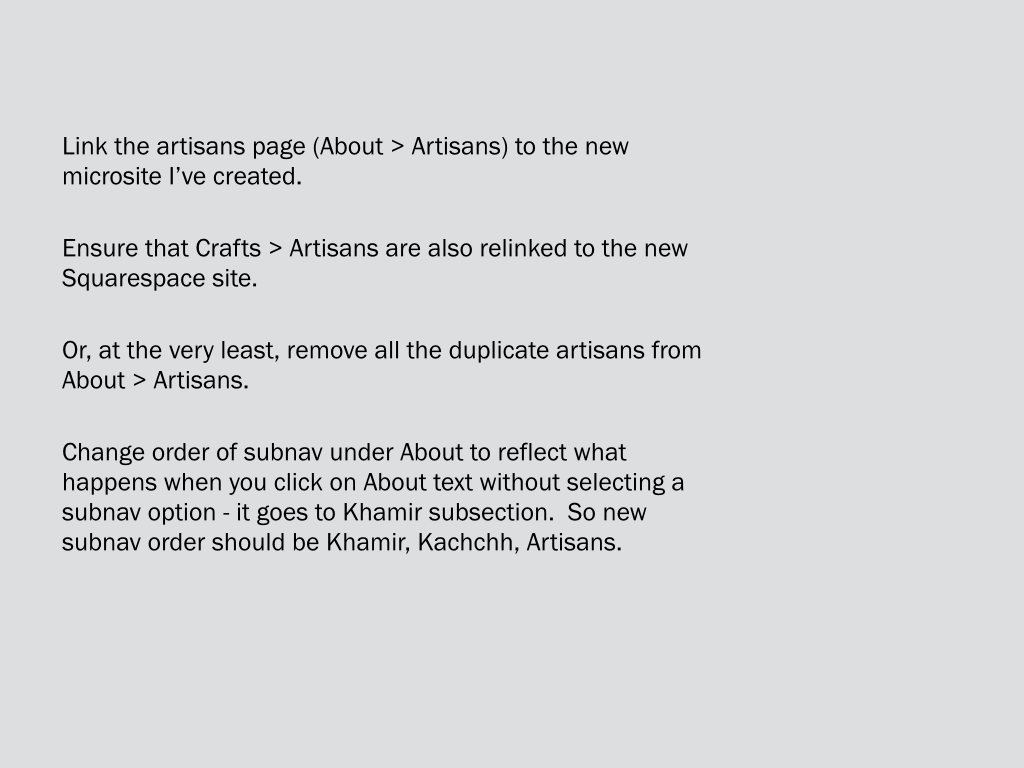

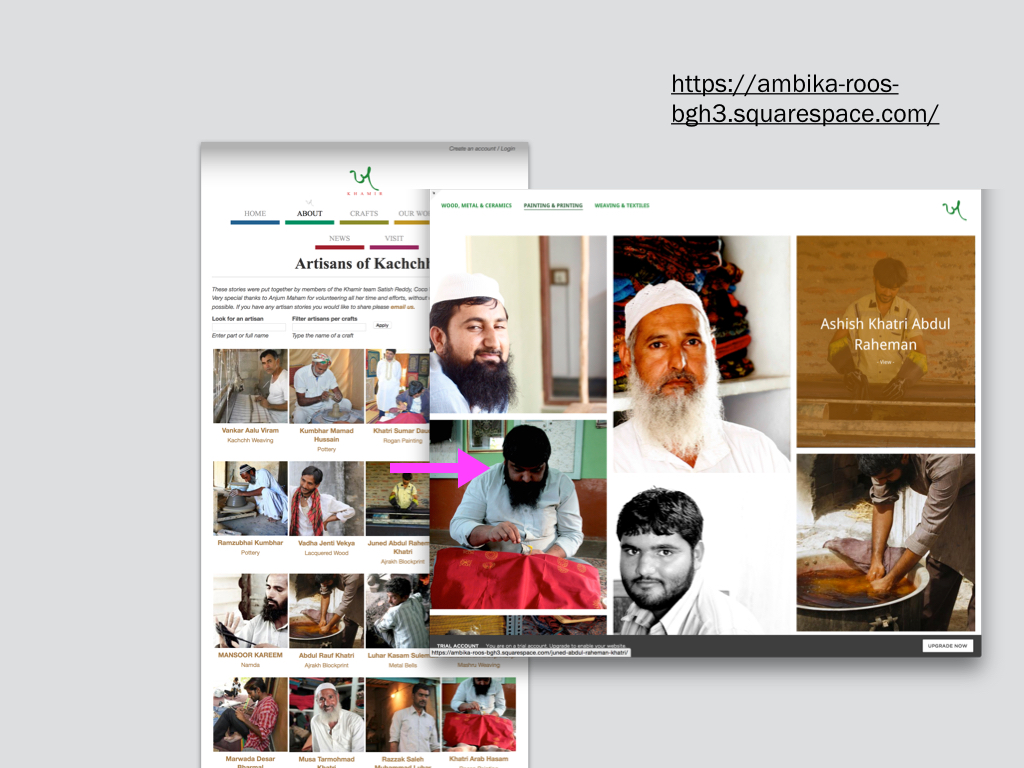

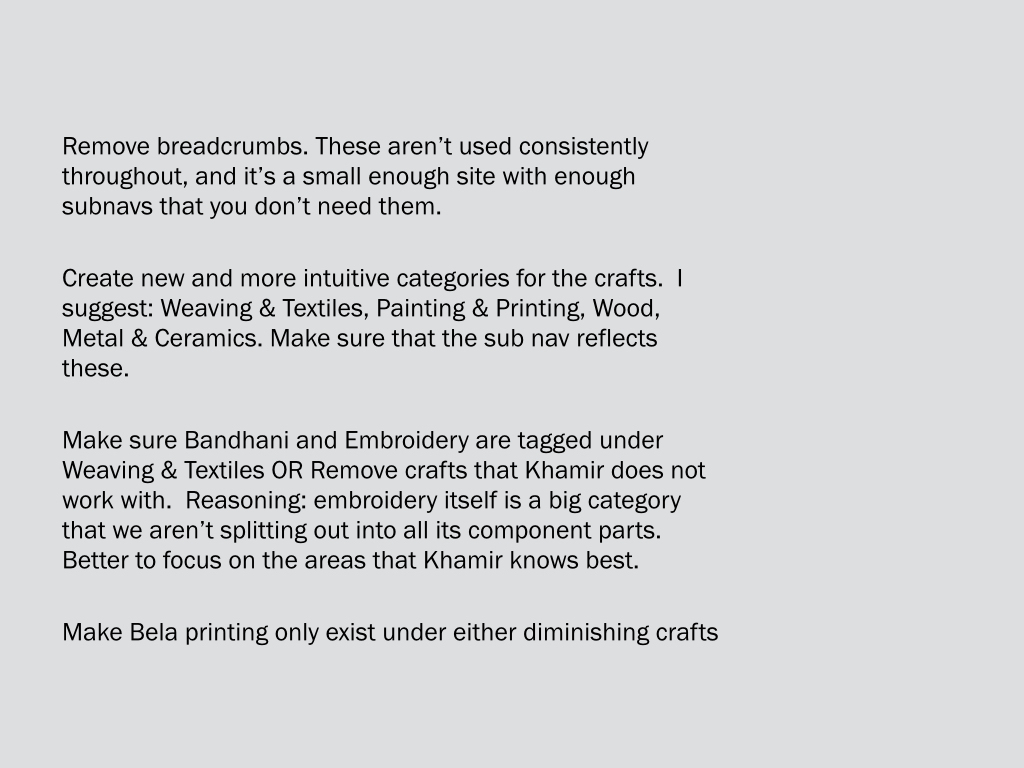

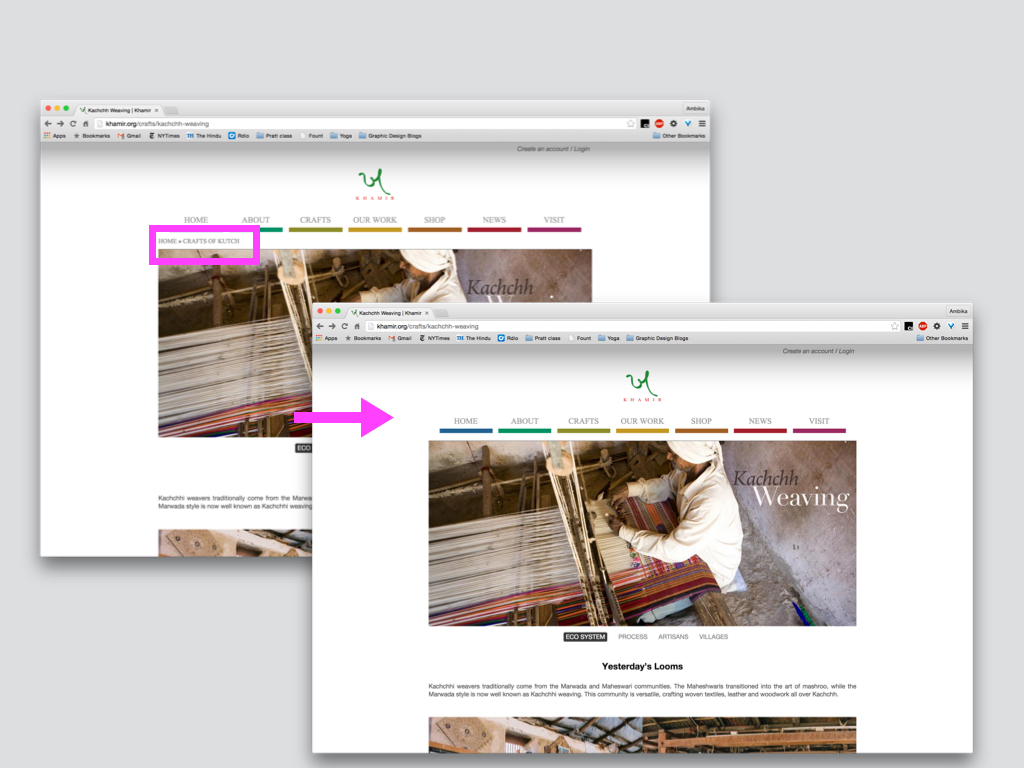

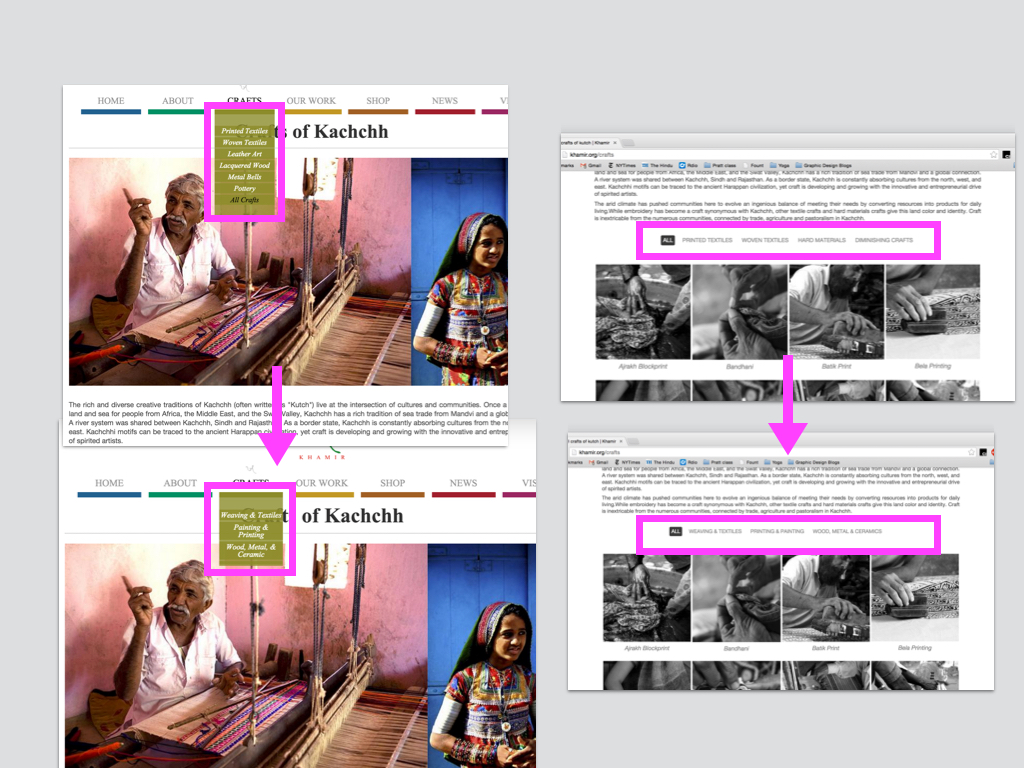

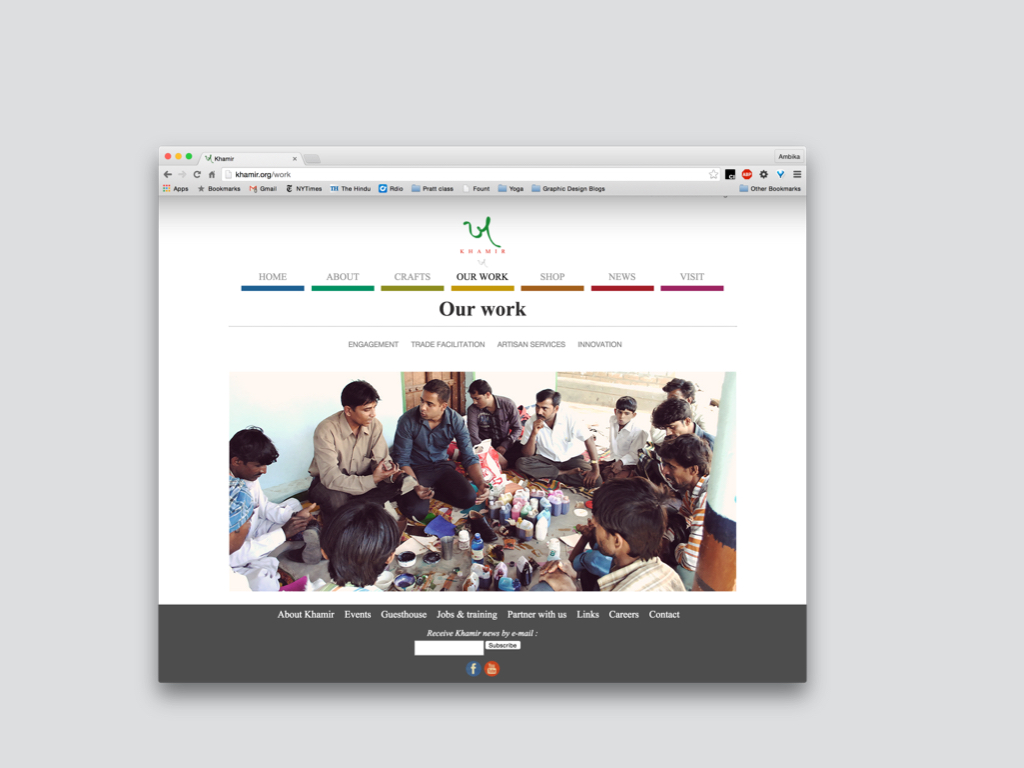

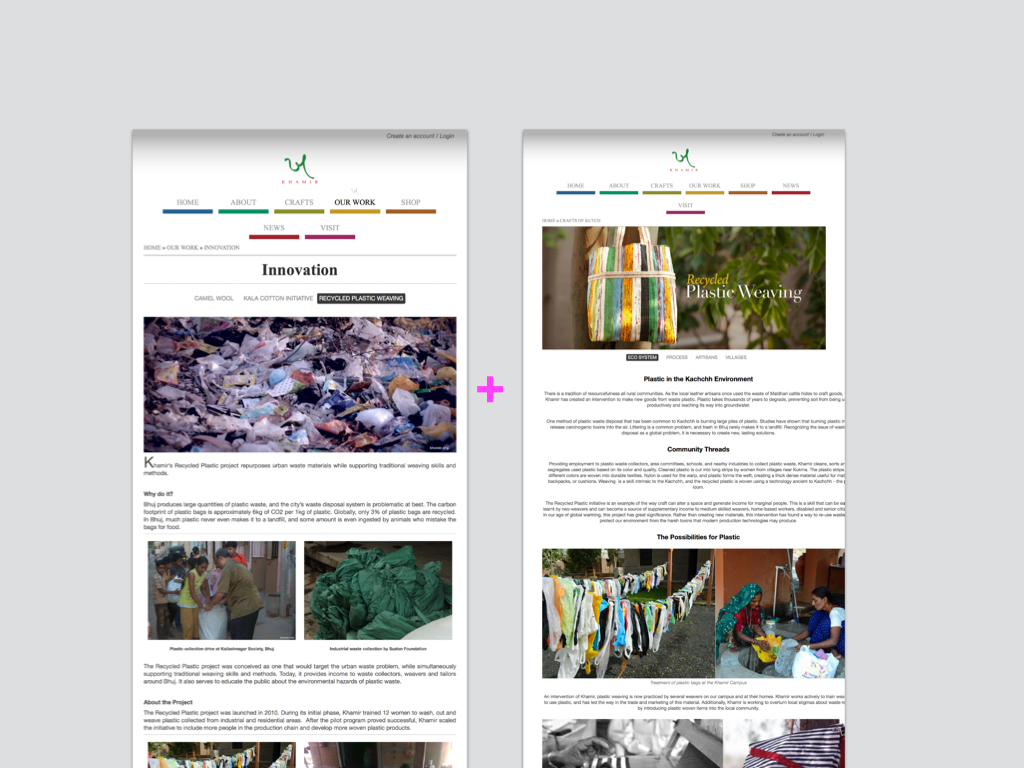

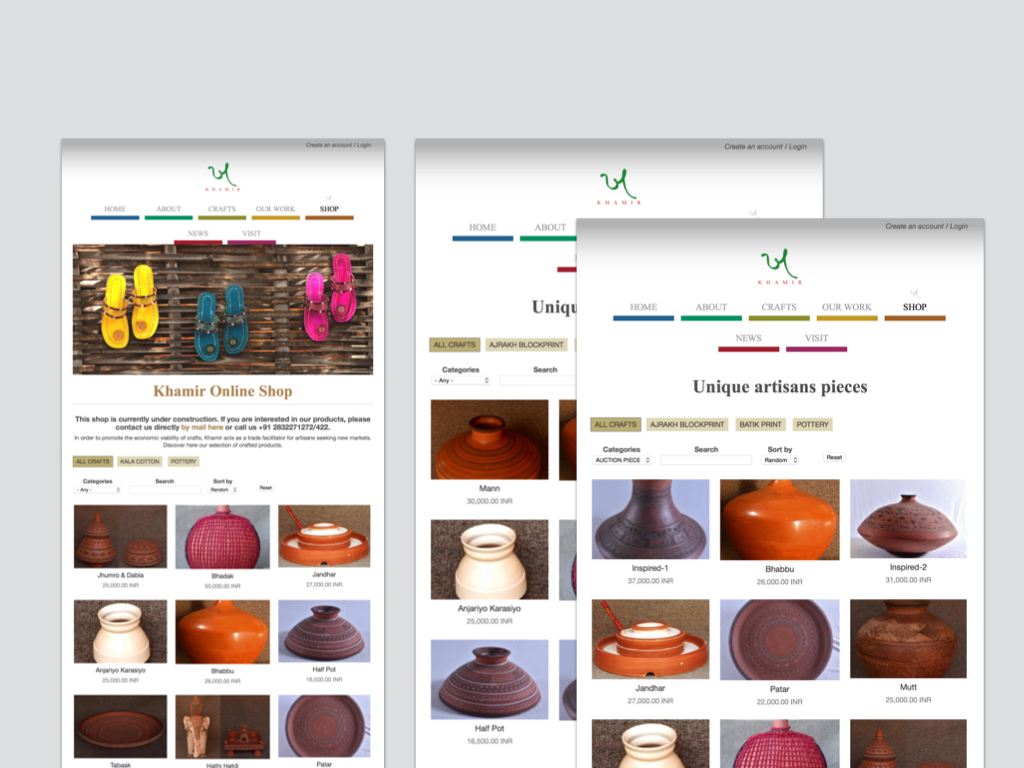

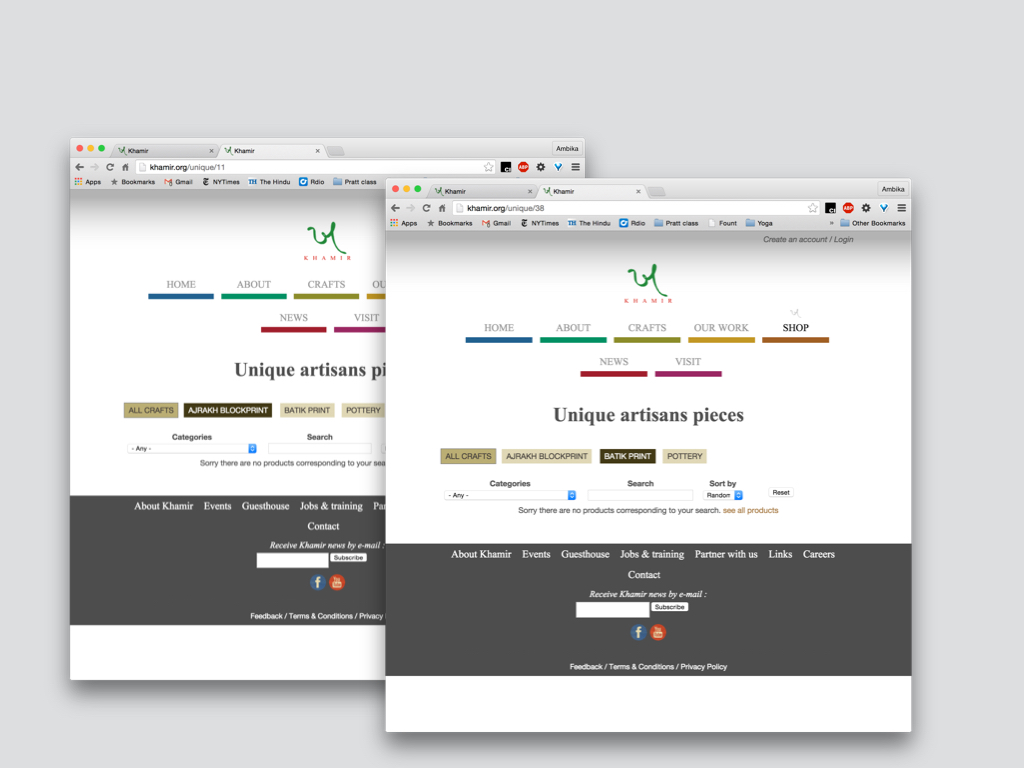

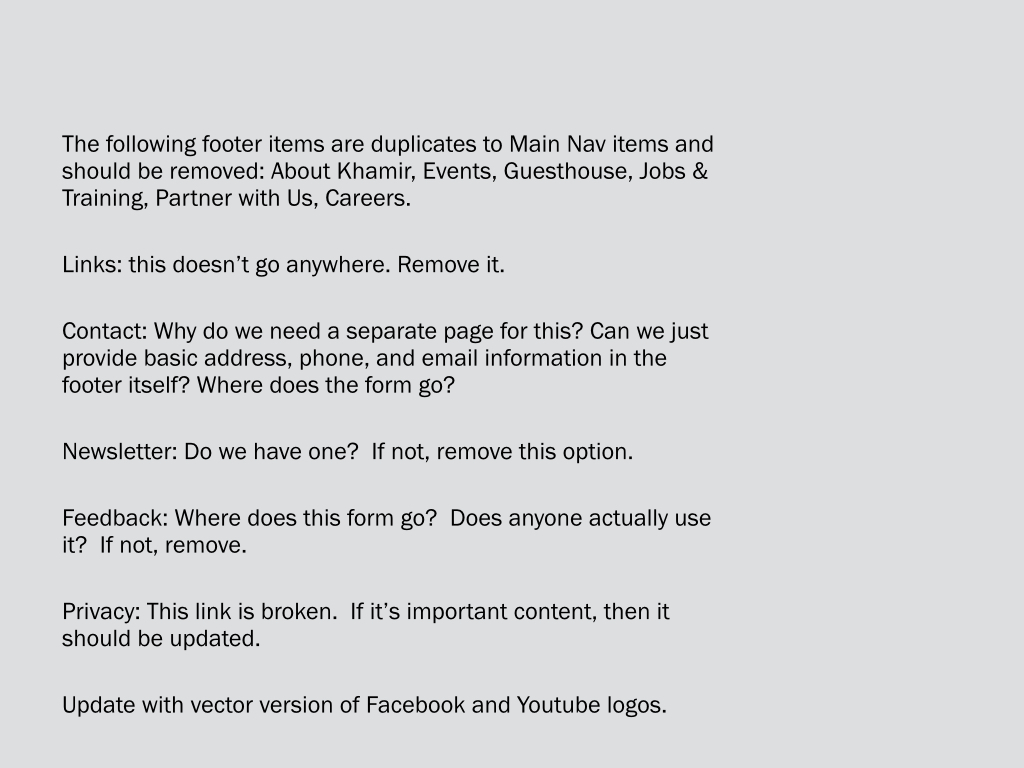

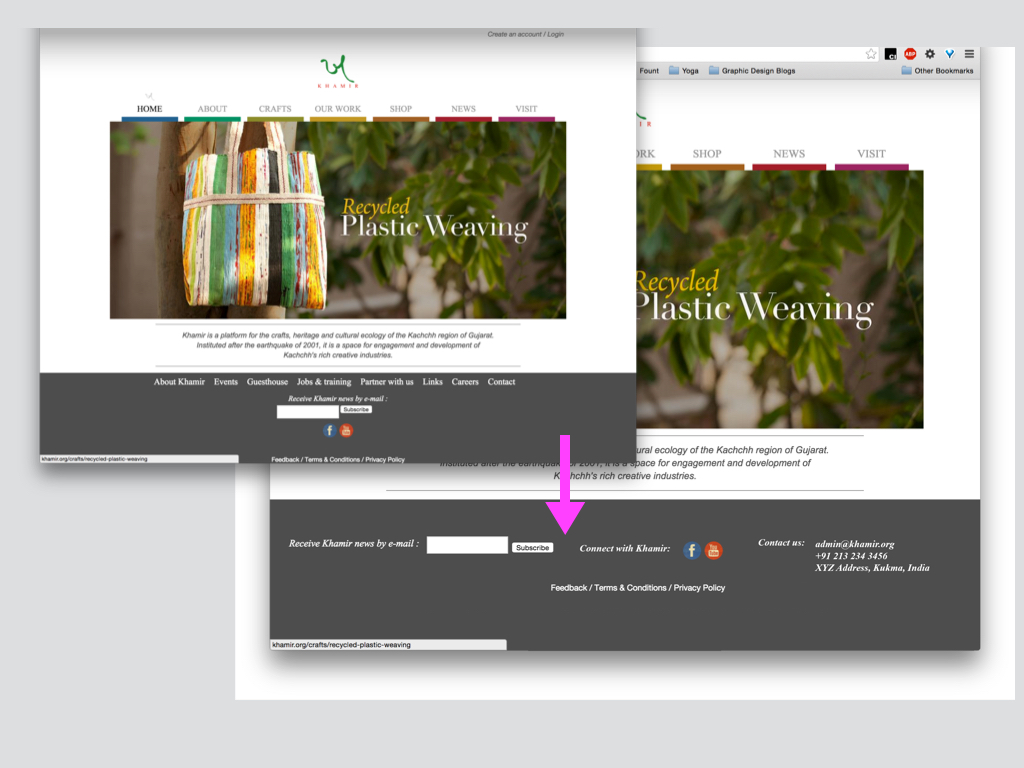

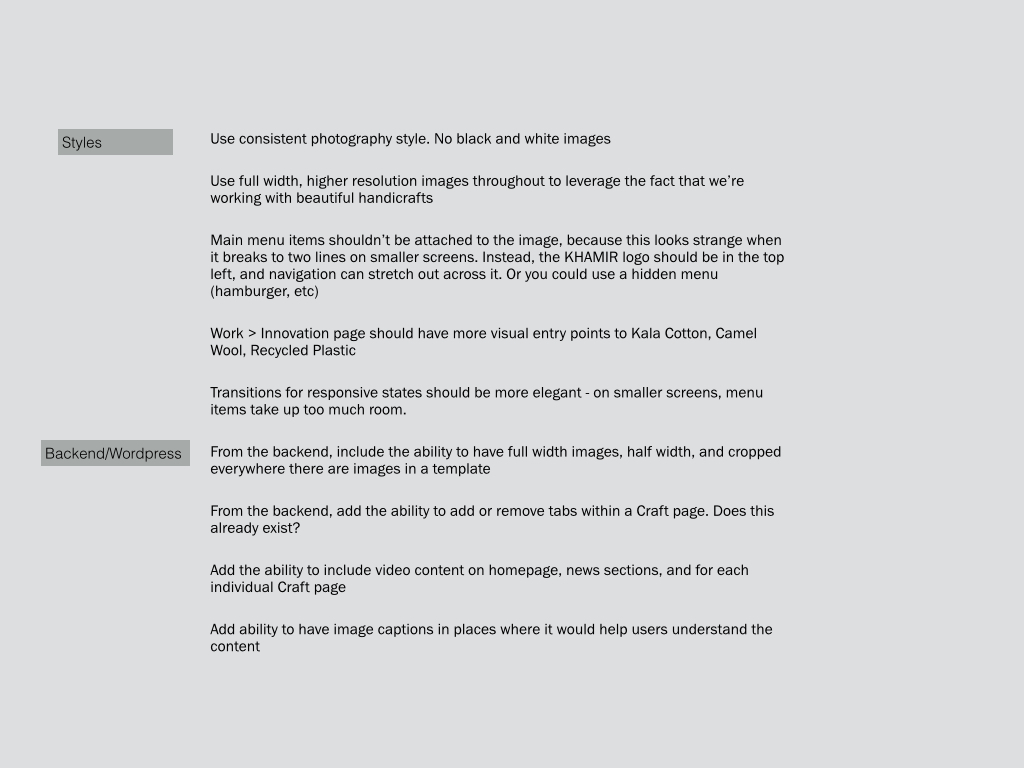

My first move when I arrived was to try and understand the whole ecoysytem of Khamir’s digital tools, starting with the website. I conducted a detailed audit of content and layout, and made some practical recommendations for improvement:

I also introduced a few tools that were new to the team, like Mailchimp for mass emails, Squarespace for new microsites, Airbnb as an option to rent out the lovely Khamir guesthouse, and Etsy as an option for improving ecommerce - all with accompanying tracking and analytics. We brainstormed some new fun ways Khamir can engage visitors online. What about a Khamir On the Grid page (onthegrid.city)? Or a map plotting the location of artisans across the region, in a design similar to the interactive map I helped create for UNICEF (sowc2015.unicef.org/map)?

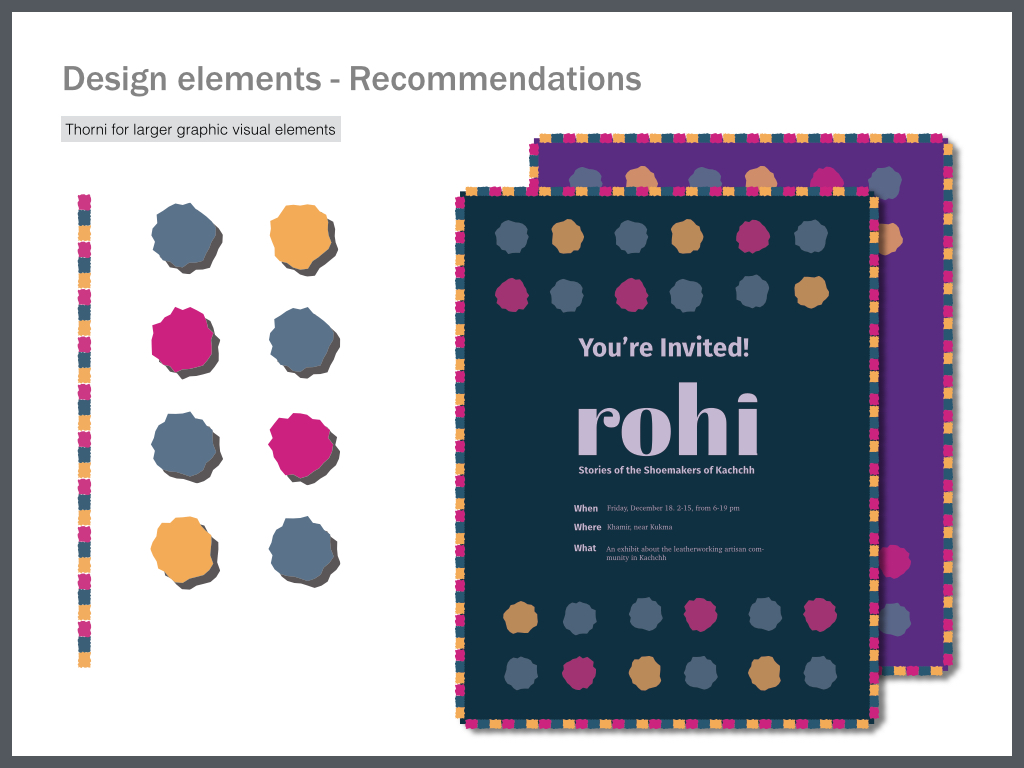

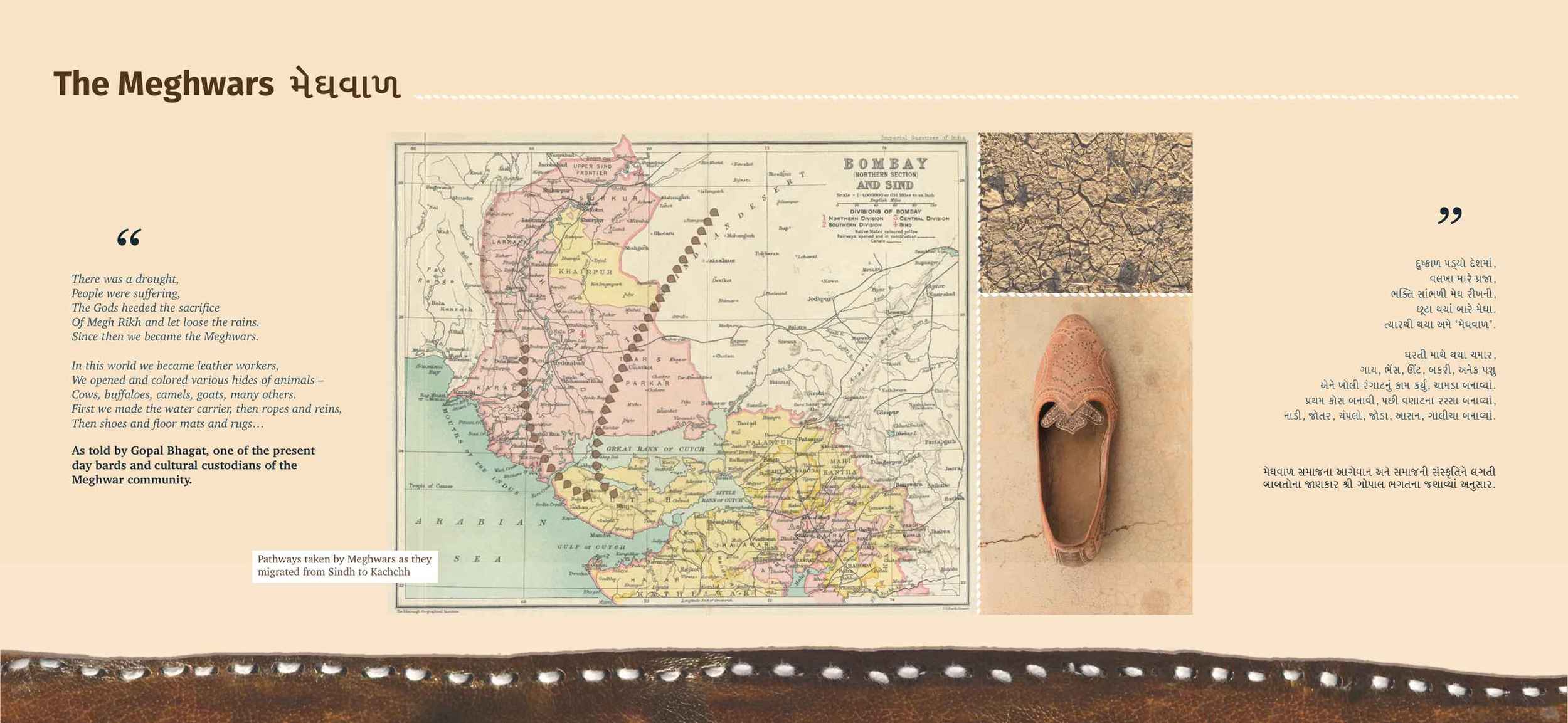

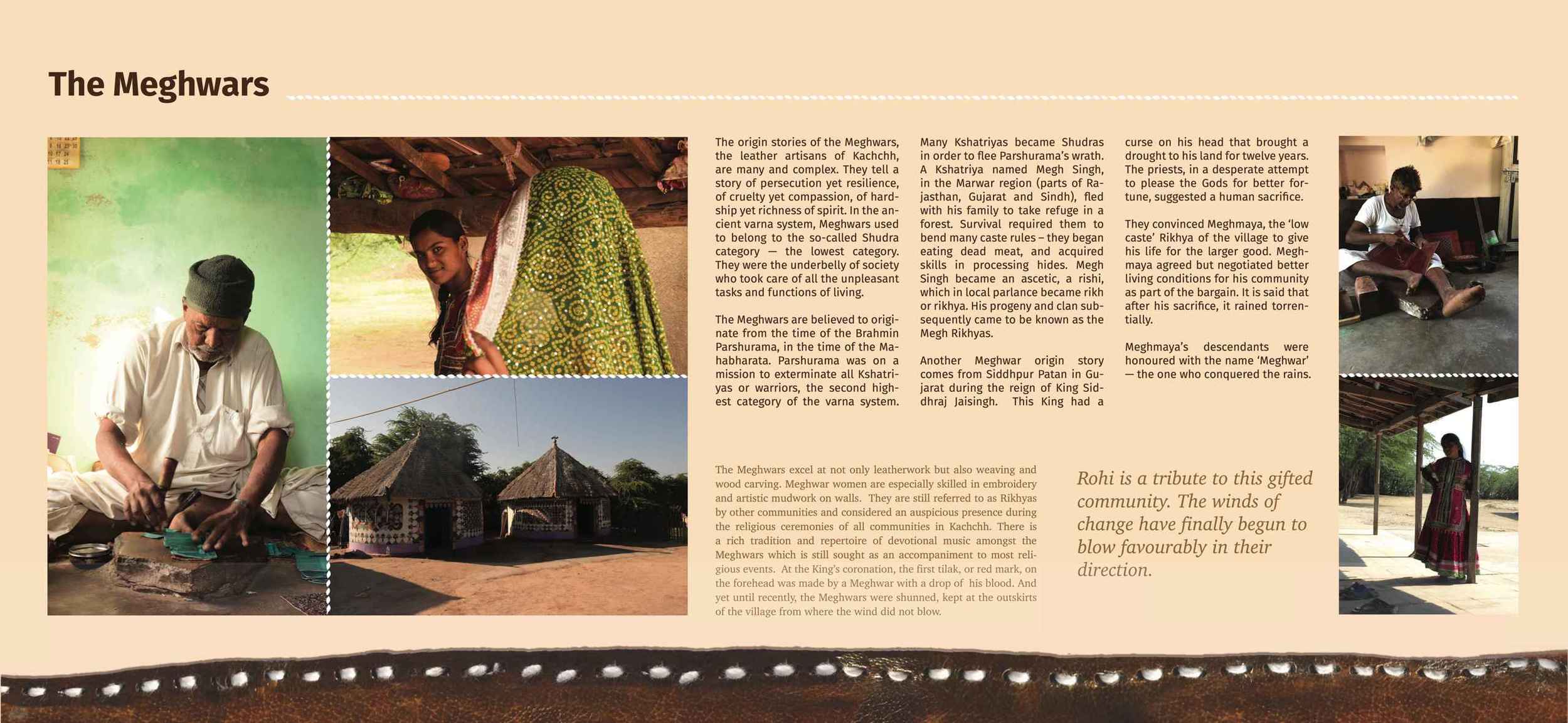

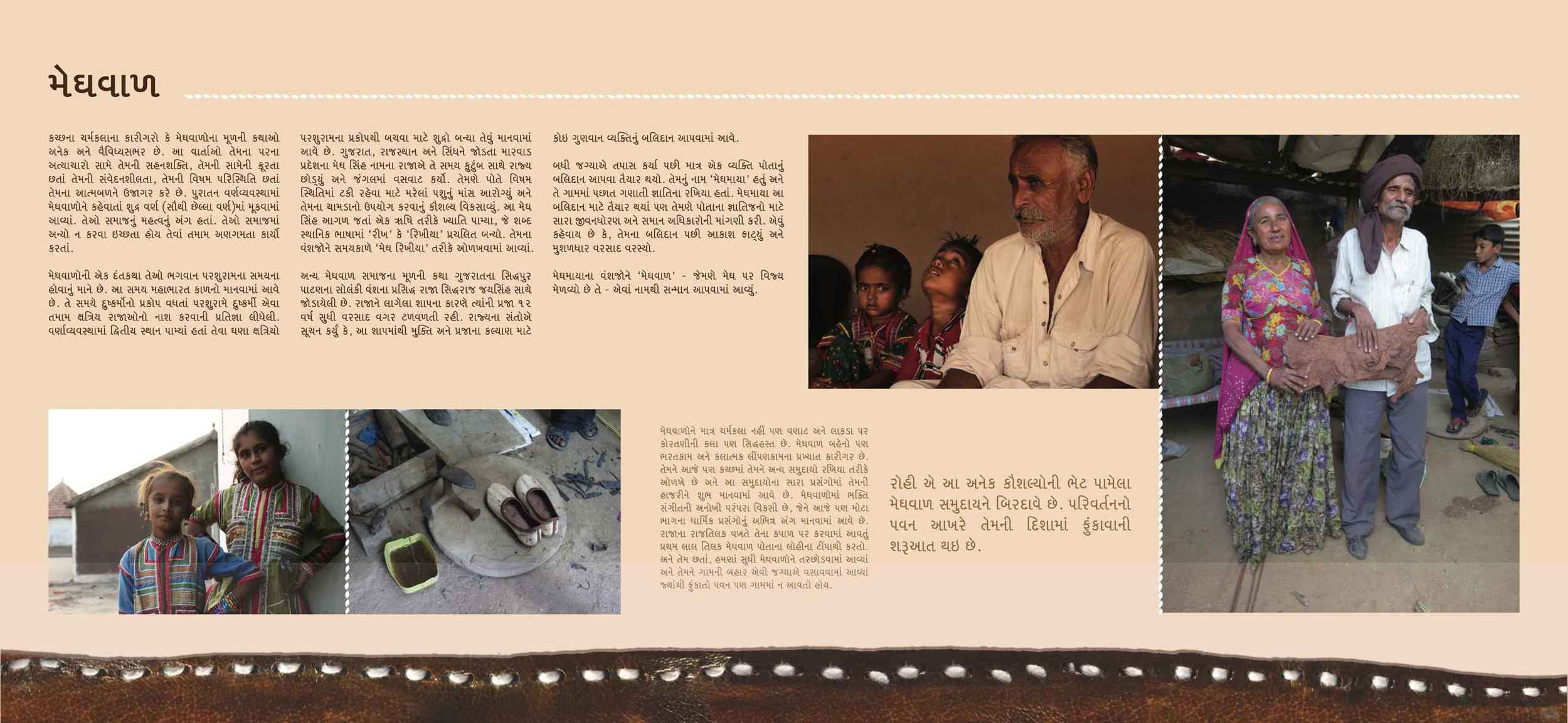

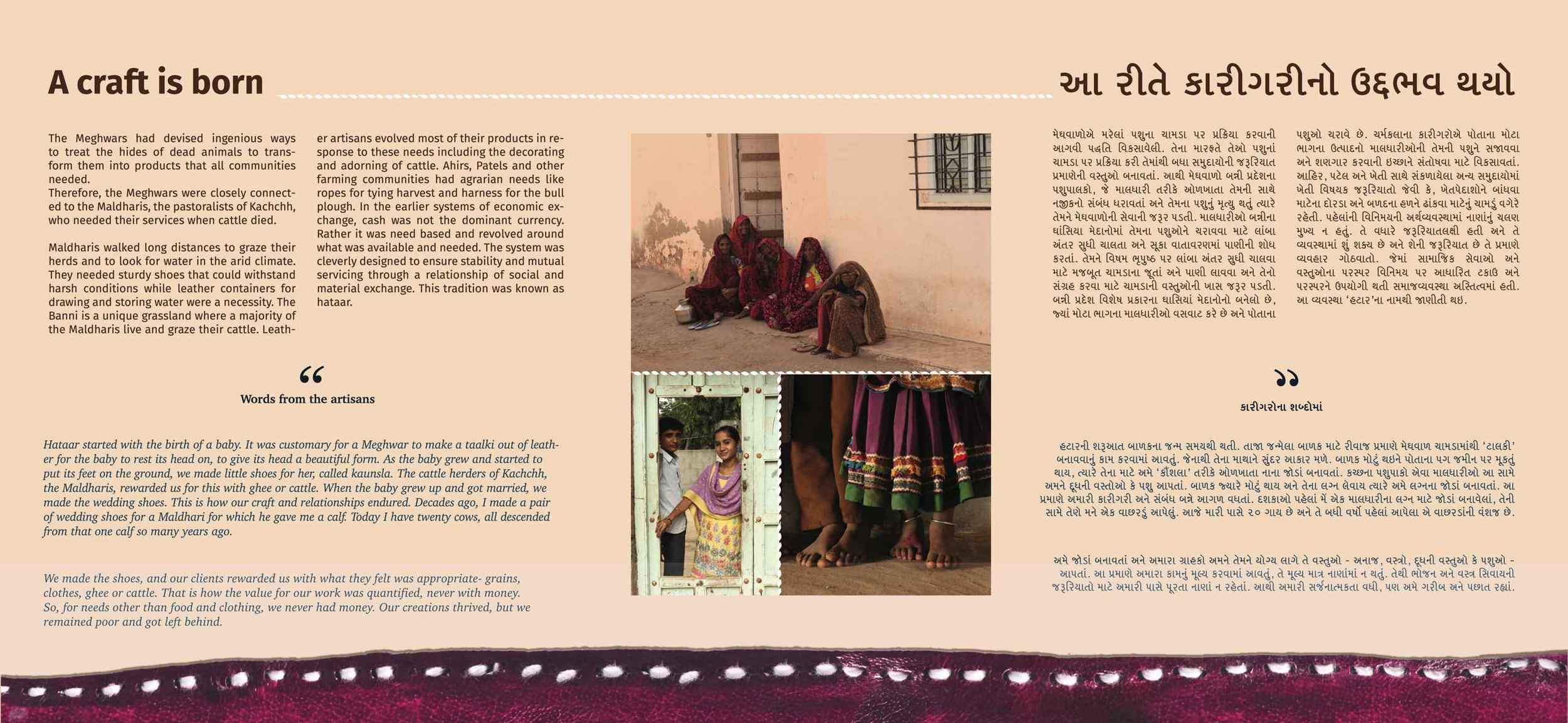

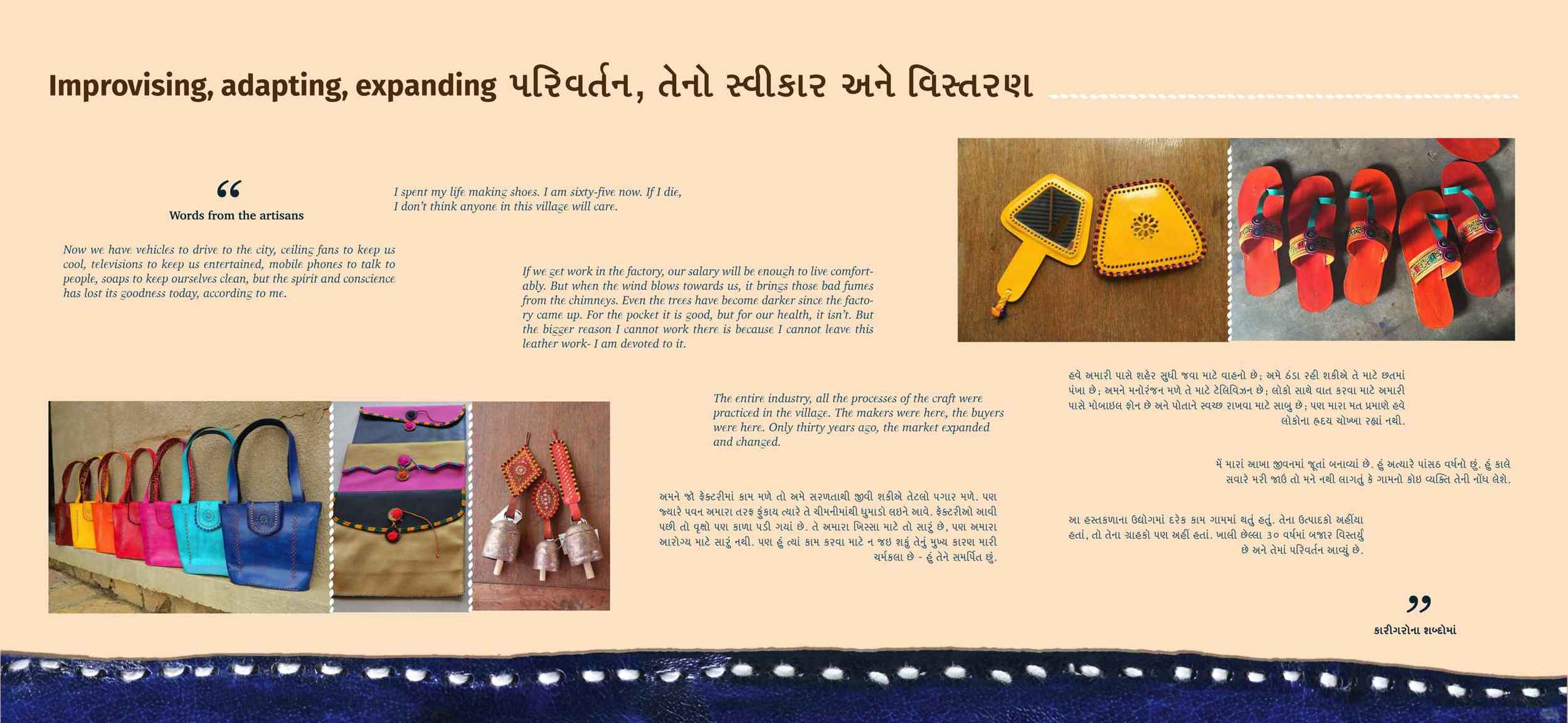

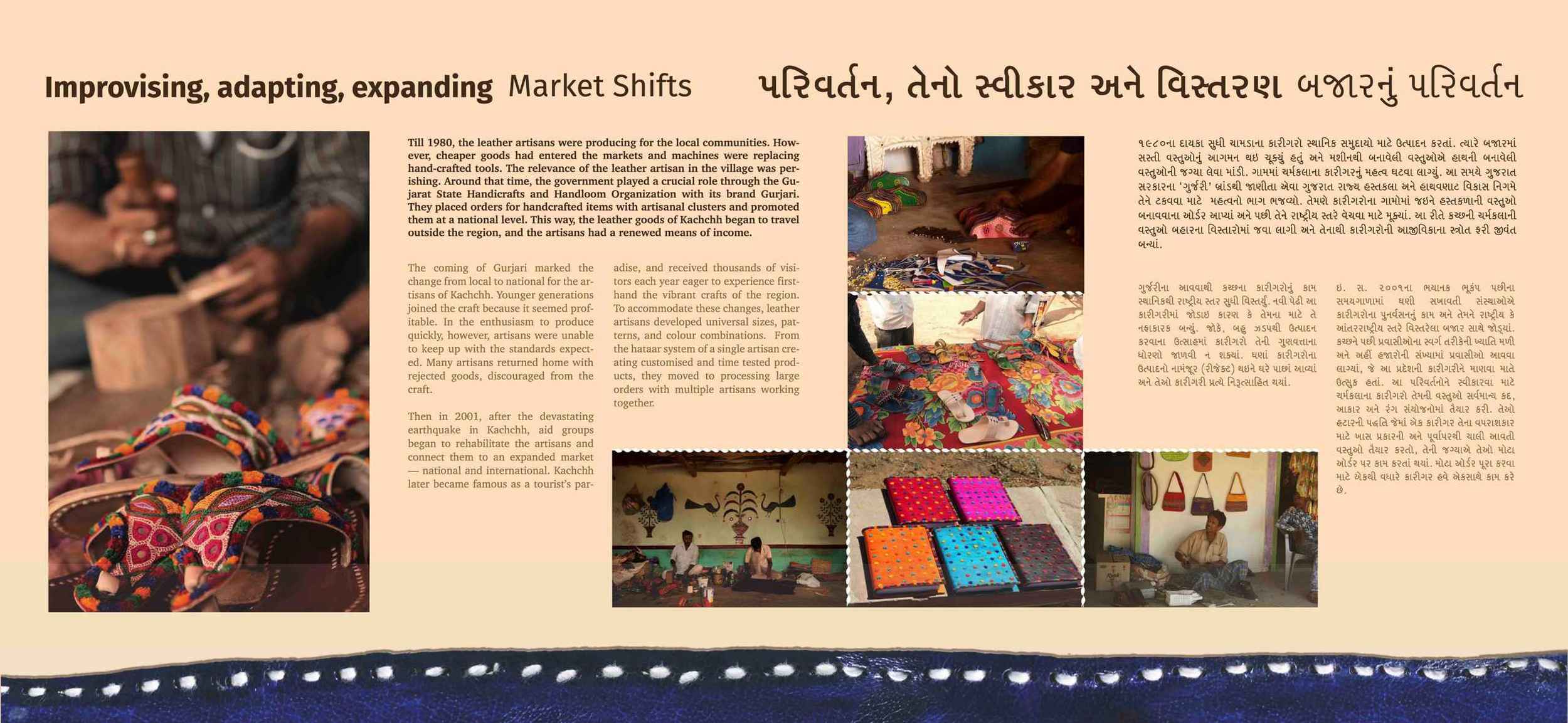

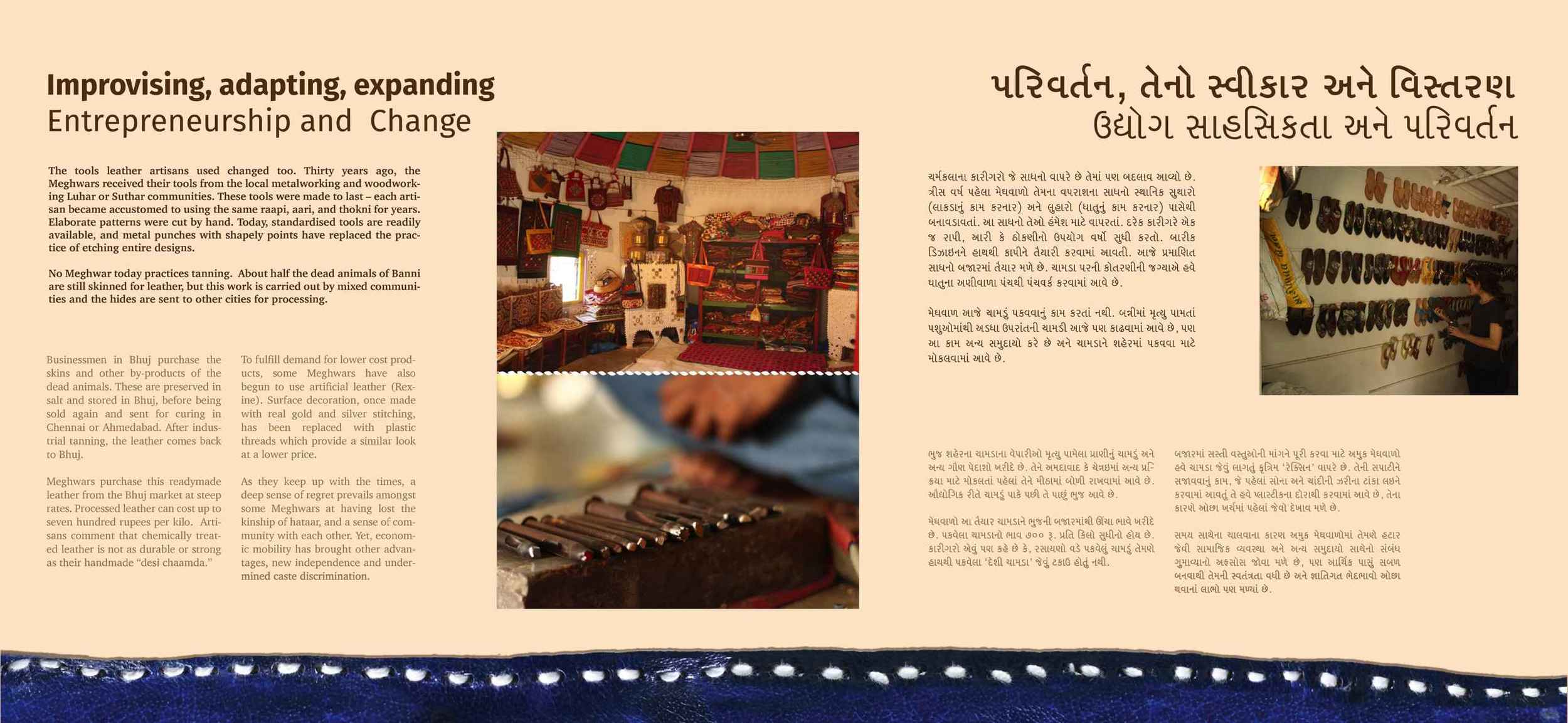

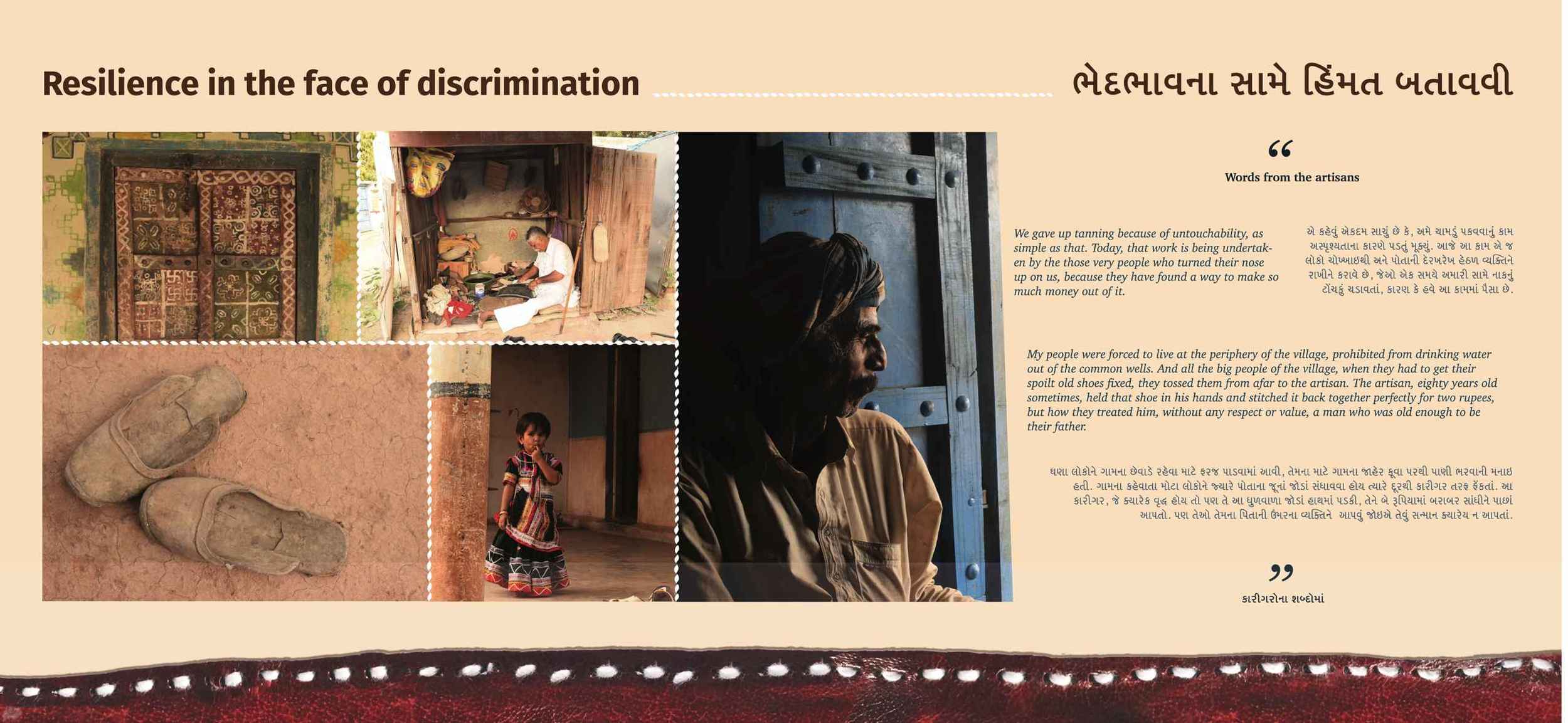

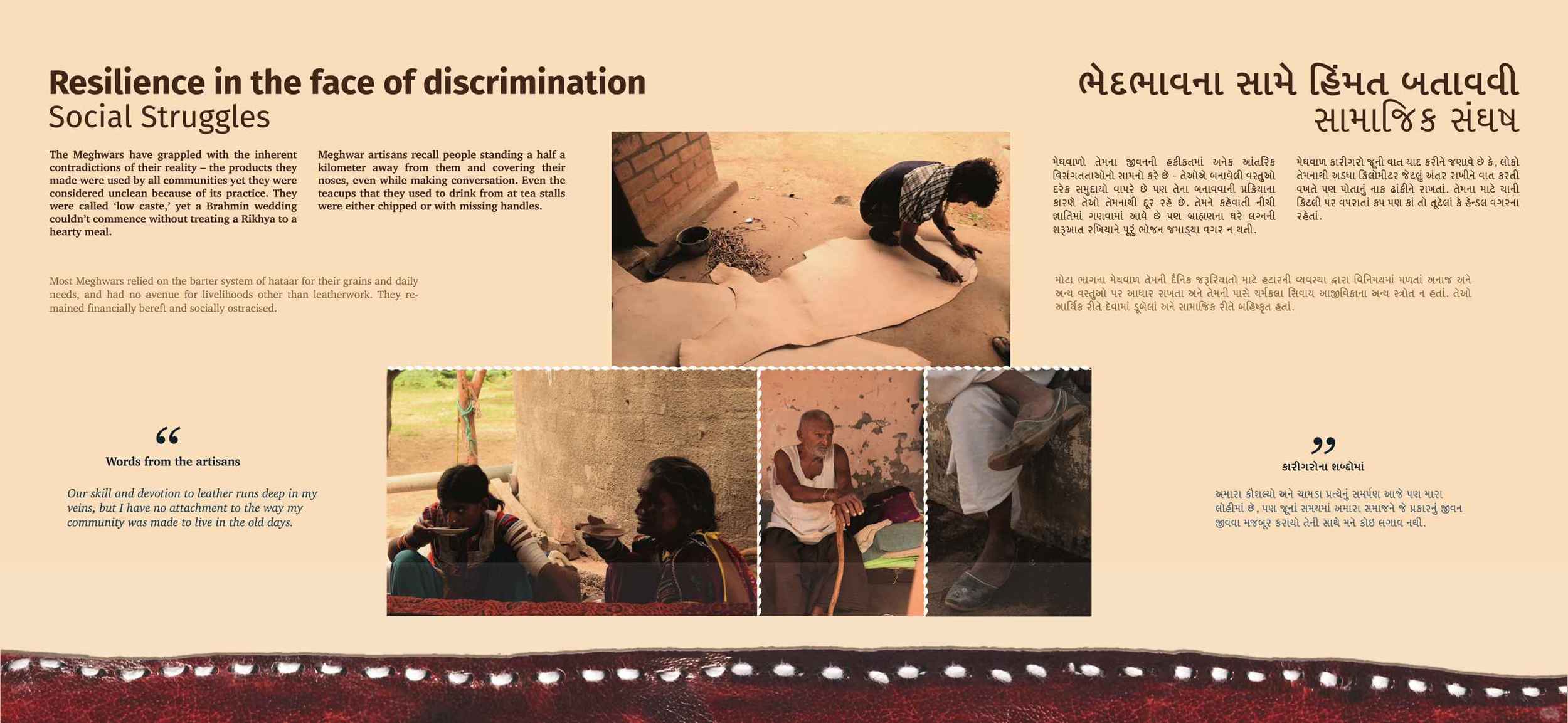

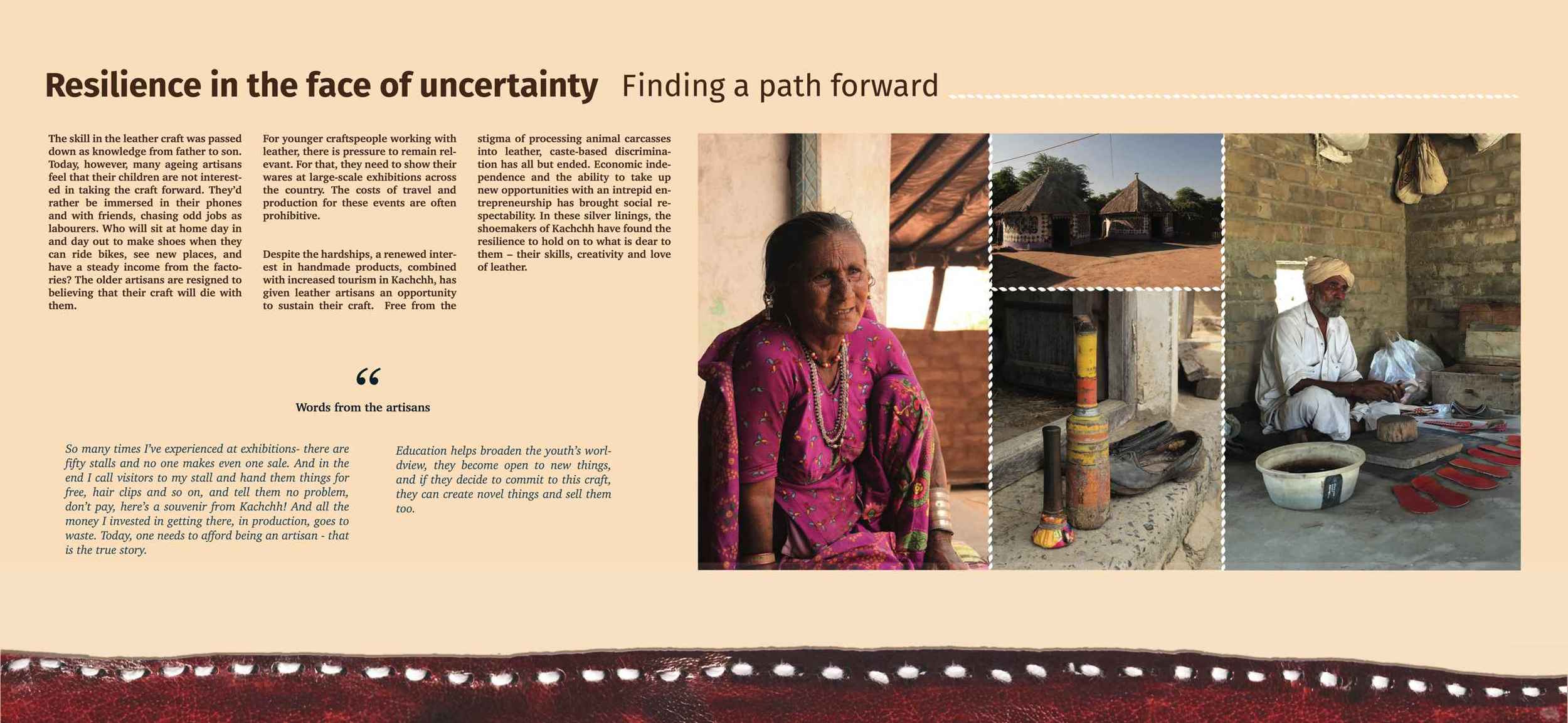

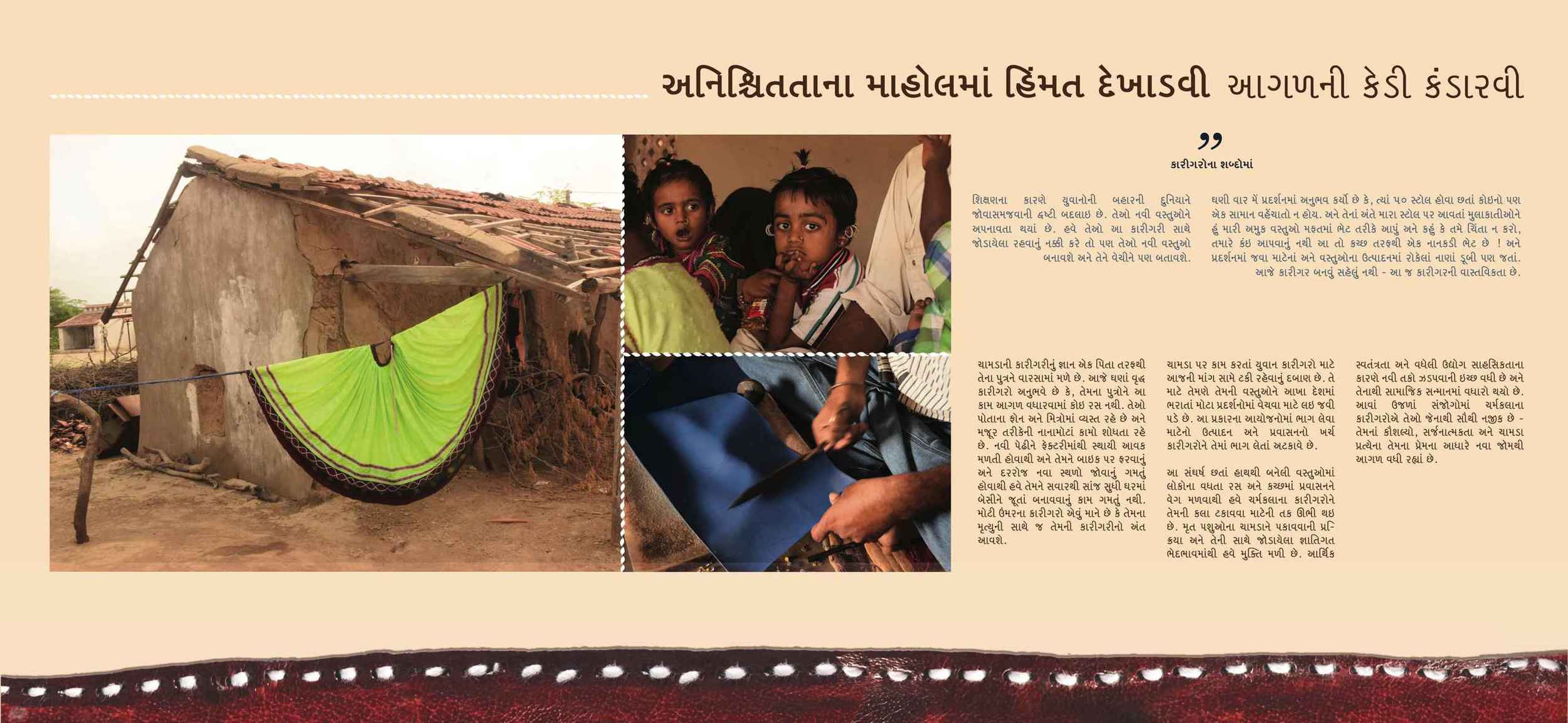

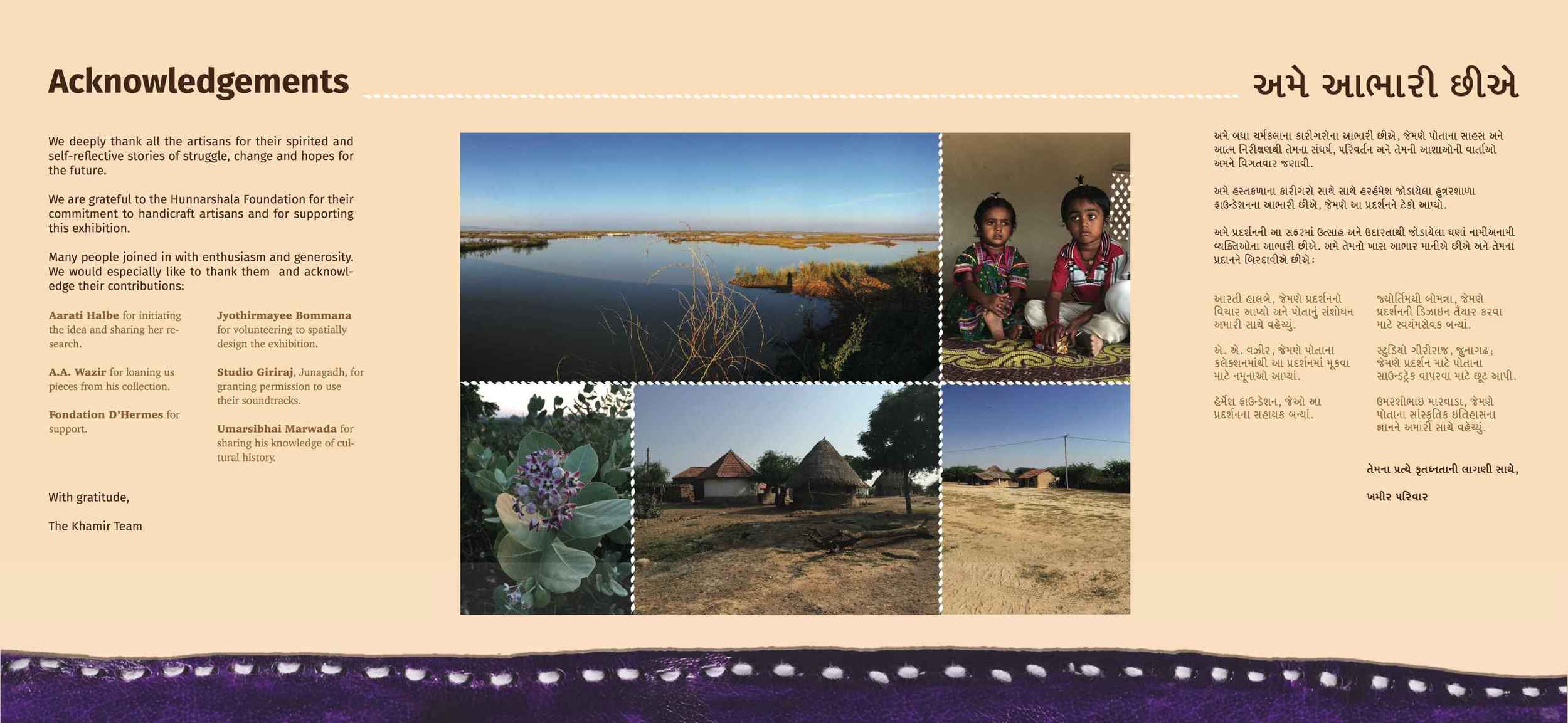

The bulk of my time has been with the team of curators who researched and designed this year’s annual exhibition on the leather artisans of Kachchh. Open to the public for two months, it’s been visited by tourists, local residents, school groups, and artisans alike. I designed a consistent visual identity for the exhibition that felt authentic to the craftsmen and was flexible enough to accommodate varied print and digital materials.

Select exhibition panels for print:

A core part of Khamir’s work is handicrafts research. Yet most of this material is not readily accessible, even in print. None of it is online where it could be of value to a broad audience of designers, anthropologists, students, and tourists.

Instead, most research is stored on a hard drive in formats that are not easily parsed, and stashed in someone’s desk. Khamir hosts many visiting designers, fellows, and interns, who complete research during their time here, and may not leave behind the raw files of their work. Last year’s exhibition on the potters of Kachchh, for example, was a massive undertaking. But for me, new to the community, it was difficult to try to find any of this knowledge.

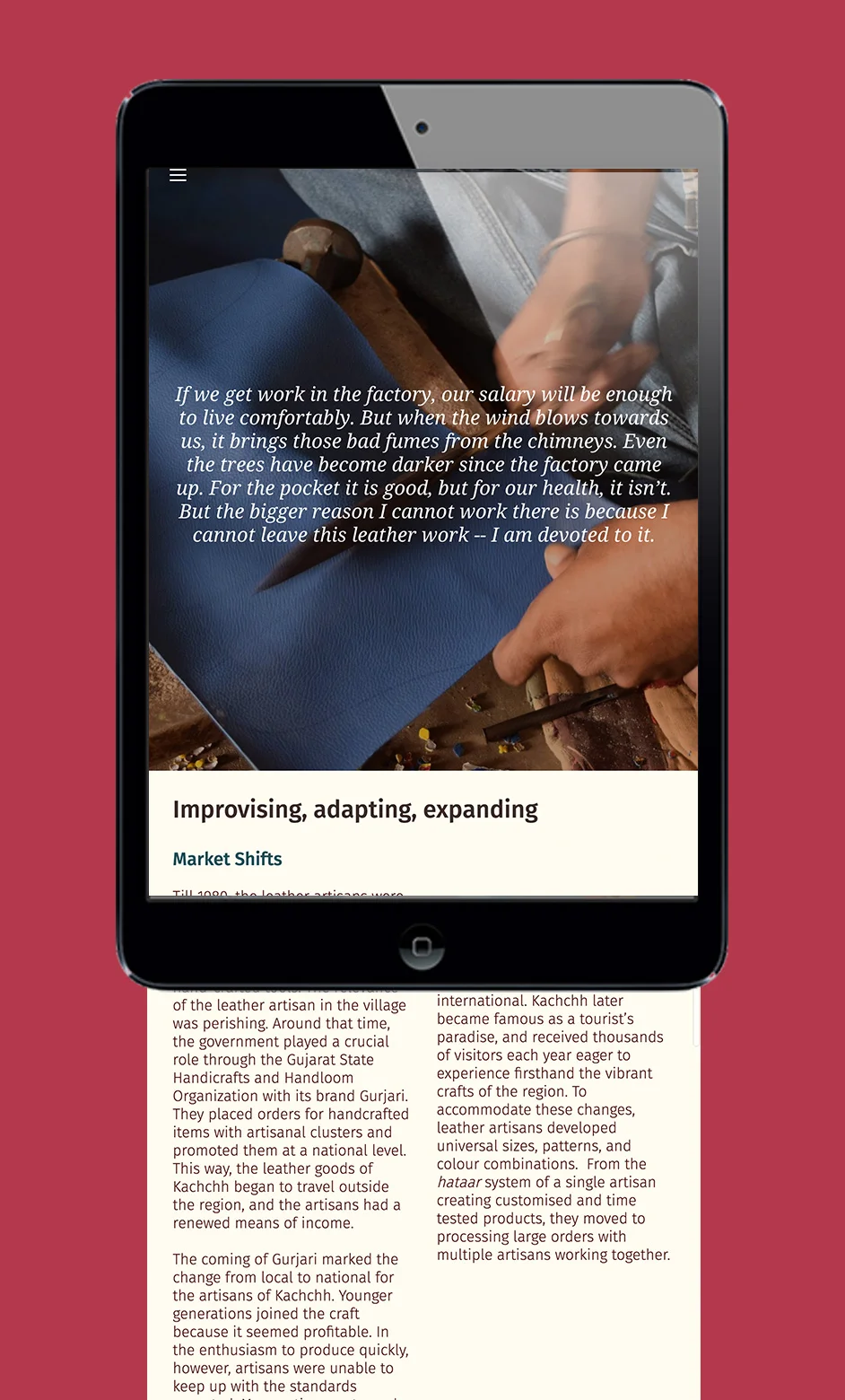

So for the first time at Khamir, I put all the research for the Rohi exhibition online, in a digital native format. You can see it at: rohi-khami.org. If the stated purpose is to promote engagement with creative industries, why not make the primary research we were collecting available to as many people as possible? Coming from a UX background in New York, there was no question in my mind that open source data helped everyone: Khamir and the artisans reach more people, researchers have information to carry their work further, tourists are intrigued by the region and plan a visit.

The team had some concerns, though. If we put all our content online, who would come visit in person? What if students copied the information and misused it without proper citation? What if designers copied the patterns developed by Kachchhi artisans over generations, and sold them for their own profit? Together with the team, I created a plan that allayed some of these fears while still pushing Khamir forward with its first digital archive. Photos of artisans, sensitive about how their image is used, have a watermark. There is a Terms of Use outlining proper guidelines for all content housed on the site. Research specifically on individual products is put online, but its password protected for now so that Khamir can control who has access to it. Making these compromises helped everyone feel comfortable with the new arrangement - and I’ve been asked now to make digital archives for all past exhibitions as well.

In coming months, I’ll be trying to push Khamir further with their digital communications and tools. I’d like to develop a living archive - that is, enabling artisans themselves to document their work. The picture below shows what I’m thinking of prototyping – but more ideas are welcome!